To the first post of the series: Deep DX – Creating DX7 sounds with AI: Part 1 – Introduction

When sourcing patch data for the machine learning model I was creating, the Yamaha DX7 was a terrific choice given the vast amount of patches freely available online. When I started out, I knew that large datasets are required in order to get decent performance from any machine learning based on neural networks, but how large is large? Would 500 patches suffice? 5000?

In the end, I collected – to my own surprise, I might add – around 50 000 patches available in either System Exclusive format, or a “raw” sysex format lacking the mandatory system exclusive header and checksum, but fairly easy to convert.

Validating the Data

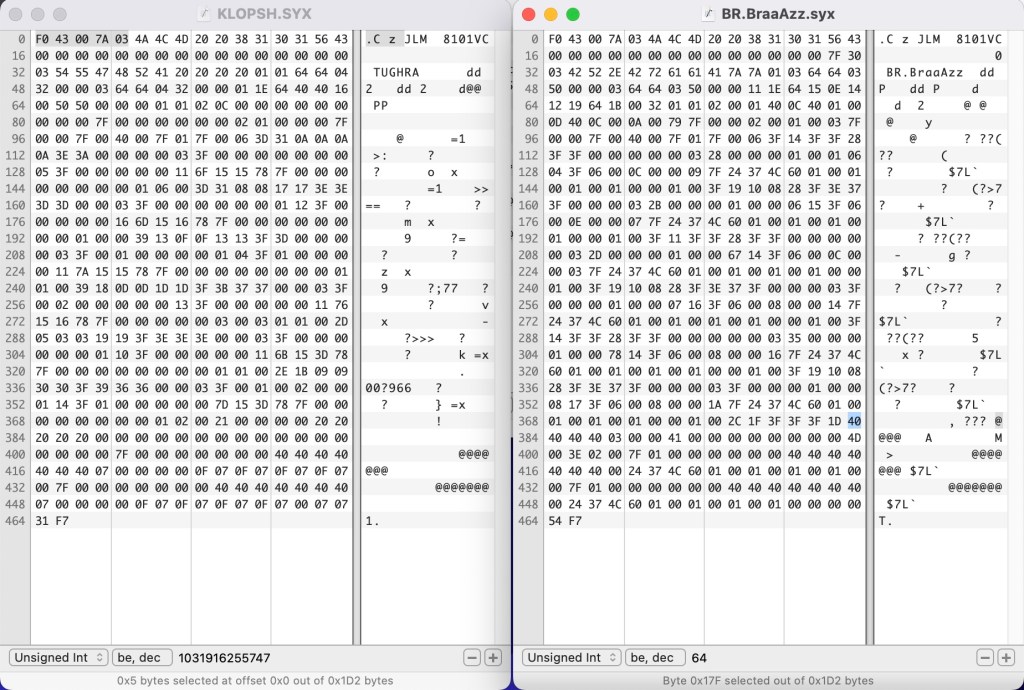

As most people familiar with “AI” or current machine learning models learn the hard way, you often end up spending vastly more time validating your data and ensuring its quality than actually training your network on it. On my Mac Studio M1, I could run 400 epochs of training in a few minutes, but I ended up spending months on writing code that would try to categorize patches according to heuristics such as name, envelope etc, while poring over endless amounts of hex dumps.

Many of the banks downloaded contained corrupt data in some form, rendering the sysex patch unintelligible to the DX7, or worse, producing horrifying FM squeals that threatened to fry my ears and made my cat upset with me.

Over the first weeks, I ended up manually removing more than 130 files, amounting to just over 4000 patches that contained garbage in some form.

Those however turned out to be the ones that were easy to weed out. Hiding beneath innocent names such as “MELLOWGTR2” I found even more corrupt patches that threatened to reduce my chances of the GAN1 stabilizing sufficiently to be able to produce anything useful. Early tests seemed to support my growing suspicion, as outcomes from training seemed to range from reasonable to just wrong, and it was hard to determine whether the cause was due to poor data, poor parametrization or both. At this point, I paused training efforts and wrote some code that tried to analyze patch data and determine whether it contained errors or not – this ended up removing another 3000 or so patches. The original dataset was now reduced by more than 10%.

From Manual Labor to Automation

When analyzing patches this way, another anomaly turned up; to my surprise, a fairly large number of patches actually didn’t have level 4 of the carrier’s envelope set to zero. In DX7 terms, this means that the sound will never fall to silence, something I rarely find useful in a musical instrument. This turned out to be a canary in the coal mine of patch exploration as it was almost 100% indicative of a faulty patch. In fact, it dawned on me that all of this effort would have been useful even if I was not embarked on a machine learning journey, as I now had a way of effectively separating the real, proper DX7 patches from the broken ones.

With the uphill battle of qualifying training data ongoing, there was also the matter of categorizing it. For this to be useful to me, the system has to be able to generate patches corresponding to a given category. For FM synthesis, the apparent categories that stand out would be pianos, bells and plucked sounds, but surely there will be patches producing other types of sounds as well? I fondly remember the useless-but-amazing GRAND PRIX and TRAIN patches from the factory cartridges, but there were also strings, bass and various synth sounds.

As luck would have it, I was to be saved by the dry professionalism of sound designers of the 80’s and 90’s. Sure, there are banks where the patches have names like ZOOT and NEBULA, but a surprising majority of patches actually have meaningful names, allowing you to infer a category or sound type just by the name itself. There’s PIANO 1, ELEC. PNO. and so on, and add to that a bit of heuristics (“slow attack on carriers are indicative of pad sounds”) and you can get fairly decent automated categorization for approximately 60-80% of the patches (depending on your categories, as we shall see)

Cat-egorization

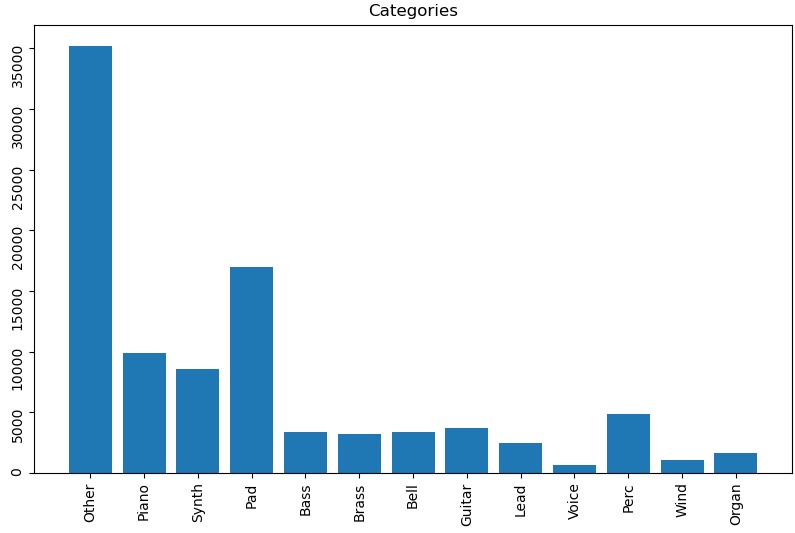

The problem will always be the sounds that have a combination of features. Is “BELL PNO” a bell sound, a piano, or both? I chose strict categorization for this experiment (making the example above a piano type patch), but a case could be made for allowing combinations (multi-hot encoding) and I might try that out in the future. As for the ZOOT sounds, I do a few manually now and then, but categorizing by ear is such a slow process that I keep them in a category named Other for now.

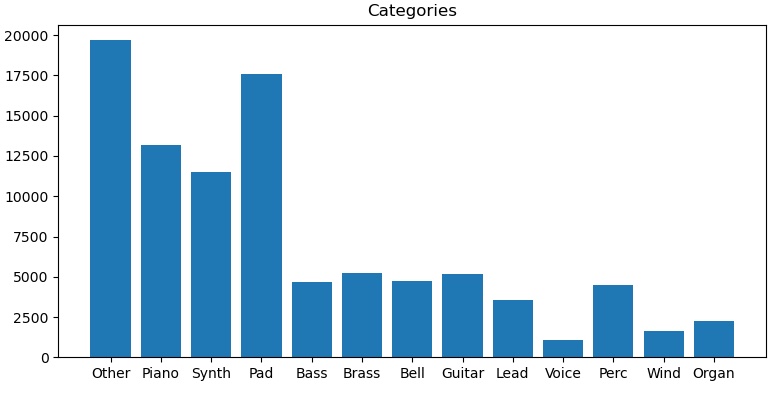

As you can see from this early attempt, most patches ended up in the “Other” category, which is of course not useful to us. Gradually improving the sorting heuristics however started to yield better results:

With Quantity Comes Quality

What I found out after a few hours of running training different variations of the network was that the categorization, or labeling in CGAN-speak, was too optimistic. Some labels, such as “Voice” or “Wind” contained too few patches to be able to produce a meaningful example space for the network to learn from.

Eventually I gave up, and went back to the drawing board. I had to reduce the number of labels, yet keep them interesting enough to make the results meaningful. I mean, I could create an application capable of only creating FM pianos, but somehow I suspected it would get boring pretty fast2.

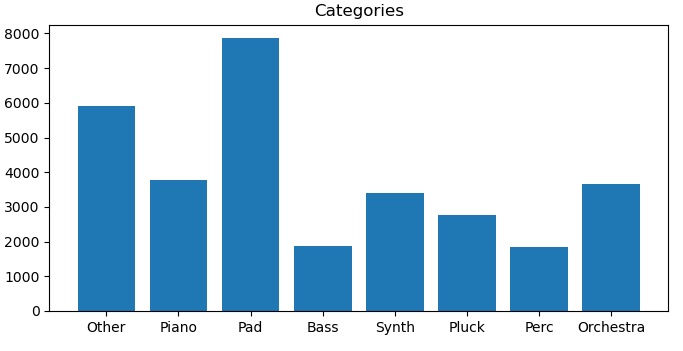

After a couple of weeks’ worth of tinkering with labels and my code for actually labeling the training data accordingly, this is what I came up with.

While not perfect by any means, it provides enough data for most labels to generate useful sounds, with the possible exception of “Bass” which is a bit hit or miss. But then, many of the plucked FM sounds actually become useful bass sounds once transposed down an octave or two, so the boundaries are not to be viewed as scientifically correct. We are generating sounds for our amusement here, after all, nothing else.

Final Reflections

A few additional observations can be made from this labeling:

- It still boggles my mind a bit that the number of Pads are almost twice that of Pianos. My money would have been on pianos when it comes to FM!

- On the other hand, the boundaries between “Plucked” and “Pianos” are subjective, at best.

- “Orchestra” offers an amalgam of anything from brass to woodwinds. The resulting patches are often cheerful and indeed “orchestral”.

- “Synth” contains everything that tried to identify themselves as emulations of analog or digital synths (more or less successfully, one might add). Unsurprisingly, this turned out to provide some of the least useful results.

- “Perc” contains anything with a snappy and short envelope, and often with slightly crazy modulation levels, thus generating patches of similar quality (that often ends up being quite useful in fact)

- Finally, the most interesting category might actually be “Other”, as it becomes a catch-all for anything not categorized by other means. The results of generating patches with this label are something of a cornucopia of surprising sounds, more often useful than not!

Satisfied with these labels, it then dawned on me that algorithm actually could be an equally useful labeling system. After all, certain types of patches tended to favor certain algorithms, so being able to generate interesting patches given a specific DX7 algorithm could actually be an alternative way to explore the FM sound space!

In the next part, we will look further into the arguments for using the DX7 algorithm as an alternative starting point, discuss how to avoid discontinuity in patch space, and take a first look at how patch data was represented in a format suitable for training a neural network!

Next post: Deep DX – Part 4: Topology of a Sound

Awesome series! I found your blog while trying a similar project, and I wonder if you’d be willing to make your code and/or data public? I’m interested trying some methods to get better and more creative sounds (e.g. RLHF, manifold morphing, maybe some evolutionary algorithms), and it would be super helpful to see how you’ve approached it.

LikeLike

Thank you! I will go over the implementation in more detail in a few upcoming posts. I believe you’re onto something interesting, I found while adapting the code for the SY77/TG77 that a combination of the trained neural net and other heuristics improved the actual patch generation even further.

LikeLike

I have been researching SY series synthesis and discovered your blog posts. I am interested in code that sends proper Sysex to the SY synths. I look forward to learning more and would certainly be interested in whether you would consider sharing that code. Thanks for documenting your project efforts, very interesting!

Tele

LikeLike

Congrats! This is indeed really interesting and well done/documented. I got my dx7(iid) on 2020 and soon realized that FM synthesis is a powerful beast that has still lots to offer, yet the HUGE parameter space makes it difficult to perform an in-depth exploration. Please, keep the updates coming, and also I find this report inspiring so I may put hands on on projects like this one.

LikeLike

[…] Deep DX – Creating DX7 Sounds with AI: Part 3 – The Data […]

LikeLike

[…] Next post: Deep DX – Creating DX7 Sounds with AI: Part 3 – The Data […]

LikeLike